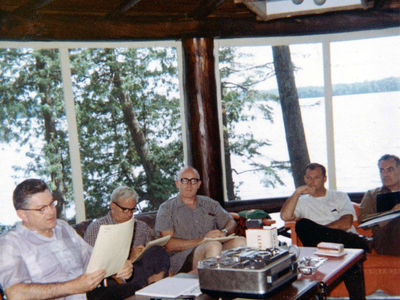

Discussion group at the 1967 Land O’Lakes meeting

Discussion group at the 1967 Land O’Lakes meeting

By Peter Cajka

Leaders of Catholic higher education became convinced in the late 1960s that the Catholic universities and colleges they oversaw had to change. Academic standards had to improve. Research needed a boost. But the traditions of Catholicism still had to be handed down to rising generations of the faithful.

In summer 1967, Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C.—at the time president of both the University of Notre Dame and of the International Federation of Catholic Universities (IFCU)—brought together a group of Catholic university administrators, leaders of religious communities, bishops, and scholars, at Land O’Lakes to discuss the issues confronting Catholic higher education. The document the group produced, known as the Land O’Lakes Statement, charted a new course for Catholic universities by calling for a deepened commitment to academic research and institutional excellence. “The Catholic university of the future will be a true modern university,” the statement declared, “but specifically Catholic in profound and creative ways for the service of society and the people of God.” The document’s framers captured the energy of the late 1960s, and historian Philip Gleason has called the statement “a symbolic manifesto that opened up a new era in American Catholic higher education” (Contending with Modernity, 317).

On September 5, 2017, the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism and the Office of the President at the University of Notre Dame together hosted a panel and lecture to commemorate the statement’s 50th anniversary. As Cushwa director Kathleen Sprows Cummings explained in her opening remarks, the Cushwa Center serves the academic community and the Church by its various efforts to connect the American Catholic past to the present. In the case of the Land O’Lakes Statement and its significance for the current moment, that effort began with an afternoon lecture by John T. McGreevy, professor of history and I.A. O’Shaughnessy Dean of the College of Arts and Letters at Notre Dame. Understanding the Land O’Lakes Statement, McGreevy argued, requires contextualization. The group that came together at a retreat house in Northern Wisconsin did so under three particular circumstances. Their meeting took place in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, which had concluded just a year and a half earlier in December 1965. McGreevy explained that the statement’s authors manifested the spirit of the conciliar document Gaudium et Spes and its attempt to “take faith into the world” and engage with other faith traditions.

Second, as the list of attendees suggests—two lay trustees of Catholic universities and John Cogley, a prominent Catholic journalist, participated—Catholic higher education was beginning to move away from clerical leadership toward faculty governance and lay trusteeship. Paul Reinert, S.J., the president of Saint Louis University, arrived at the Land O’Lakes meeting having recently transferred governance to a lay board of trustees at his home institution. The Land O’Lakes meeting unfolded in the midst of a significant transfer of power from the clergy to the laity.

Finally, Land O’Lakes had a global context. Similar meetings took place in Paris, Manila, and Columbia under the auspices of the IFCU. Reports at these four meetings were prepared in advance of the 1968 General Assembly of the IFCU held in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. The list of invitees reflected the international dimensions of the North American meeting itself: Rev. Philippe MacGregor, S.J., rector of the Pontifica Universidad Catolica in Peru, Rev. Theodore E. McCarrick, then-president of the Catholic University of Puerto Rico, and M. L’abbé Lorenzo Roy, Vice-Rector of Laval University in Quebec, all made the trip to Wisconsin.

The participants did not anticipate the crisis in vocations and the falling away of significant lay populations from the church, McGreevy noted, but the vision crafted at Land O’Lakes regarding engagement with the world and academic excellence has proved a success in more ways than one. The commitment to excellence and globalism, McGreevy said, has made Catholic institutions “better at being Catholic”—both lowercase “catholic,” or universal, and uppercase “Catholic,” in the sense of handing on a faith tradition.

Following McGreevy’s lecture, a panel discussion featured brief talks by five university presidents on the legacy of Land O’Lakes and the contemporary state of Catholic higher education. Each president brought unique perspectives to bear. Rev. Joseph McShane, S.J., president of Fordham University, situated the statement in continuity with the American Catholic past. McShane explained how Archbishop John Hughes of New York founded Fordham in 1841 for two reasons: to preserve the faith and to provide Catholic immigrants access to the corridors of American power. Catholic institutions had always pursued the kinds of excellence that would help their charges attain success in wider society. The Land O’Lakes Statement entered this deeper stream of American Catholic history in 1967. McShane called this sort of excellence an “apostolic value.”

Julie H. Sullivan

Julie H. Sullivan

Julie Sullivan, the first lay and woman president of the University of St. Thomas, asked whether “Catholic” and “university” were always to be held in tension. Sullivan argued that we live in a moment when both the Church and American society are incredibly polarized. The Land O’Lakes Statement continues to inspire Catholic institutions of higher education to build bridges within the Church as well as between the Church and the world. In bringing the words “Catholic” and “university” together to build institutions of both faith and research, Sullivan said, Catholic universities have an opportunity to demonstrate reconciliation and solidarity in a nation torn by polarization and harsh partisanship.

Rev. William P. Leahy S.J., president of Boston College, spoke third on the panel. He addressed the often-heard criticism of Land O’Lakes that it contributed to the secularization of Catholic life by severing the links between Catholic universities and the hierarchy. Leahy argued that the document’s signatories were not seeking to distance universities from the Church. The document’s now-infamous call for “true autonomy and academic freedom in the face of authority of whatever kind, lay or clerical,” Leahy suggested, meant more for the politics of federal funding than it did for the Magisterium. He explained that in 1967 Catholic university presidents like Paul Reinert were concerned with recent Supreme Court decisions that denied federal funding to “sectarian” universities. Leahy argued that to understand the words “true autonomy” the context of federal funding had to be taken into account. Leahy also criticized the statement’s writers for overestimating the role theology could readily play in the modern Catholic university. It is extremely difficult for theology on its own to permeate the life of a Catholic university in the way they assumed it could, he observed.

Patricia McGuire

Patricia McGuire

Patricia McGuire, president of Trinity Washington University since 1989, noted the limitations of the group gathered at Land O’Lakes. No women were invited to the meeting. Nor did any African Americans, Asians, or Latinos—the Church’s rising demographic bases—attend. The changes in Catholic higher education that brought 26 men to a remote retreat venue in Wisconsin were also afoot at Catholic women’s colleges like Trinity. The women religious who ran these schools grappled with challenges in enrollment strategies, faculty appointment procedures, and the laicization of boards. Though the framers of Land O’Lakes may not have imagined a Catholicism in the United States as diverse as it is today, McGuire noted, the text’s emphasis on engagement still informs the Catholic commitment to social justice. Land O’Lakes, despite its limitations, helped to make possible Catholic higher education’s mission to women of color and increasingly diverse immigrant populations.

Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., president of the University of Notre Dame, spoke last on the panel. A philosopher by training with interests in the 13th-century origins of the Catholic university, Jenkins offered the long view of Church history as it pertained to the Land O’Lakes Statement. There has always existed an inevitable tension between the Church and the university, he observed. The words of the Gospel and the Magisterium can be marked by a stunning clarity, but the Catholic university is designed to raise questions and offer different perspectives. The Archbishop of Paris even had reservations about Thomas Aquinas’s reliance on Aristotle, Jenkins pointed out. Catholic universities continue to foster this creative tension between the clarity of Church teaching and new understandings using the powers of reason. The framers of the Land O’Lakes Statement, Jenkins said, rearticulated this classic tension between faith and reason for a 20th-century context.

The discussion that followed featured questions from Notre Dame students of Ryan Hall, Dunn Hall, and a class that read and discussed the statement together in advance. Students raised questions regarding tensions between “jobs” and “vocations,” the university’s duty to study the Church itself, and the place of women in contemporary Catholic higher education.

The Land O’Lakes Statement is a document often discussed but hardly ever read with the care it deserves. On its 50th anniversary, students, historians, and administrators came together to discern the statement’s multiple contexts and its continuities with the deep and more recent past of Catholic higher education. Panelists probed words and phrases for their meaning in 1967 and candidly addressed the document’s limitations. The statement’s closing words remind faculty, students, administrators, and staff that our Catholic institutions must remain dynamic and open to the signs of the times: “The evolving nature of the Catholic university will necessitate basic reorganizations of structure in order not only to achieve a greater internal cooperation and participation, but also to share the responsibility of direction more broadly and to enlist wider support. A great deal of study and experimentation will be necessary to carry out these changes, but changes of this kind are essential for the future of the Catholic university.&rdquo

Peter Cajka is a postdoctoral research associate with the Cushwa Center.

Originally published by at cushwa.nd.edu on October 12, 2017.